The Life of Significant Soil

The childhood summer home of Nobel Prize-winning poet and author T.S. Eliot is reborn as a writer’s retreat

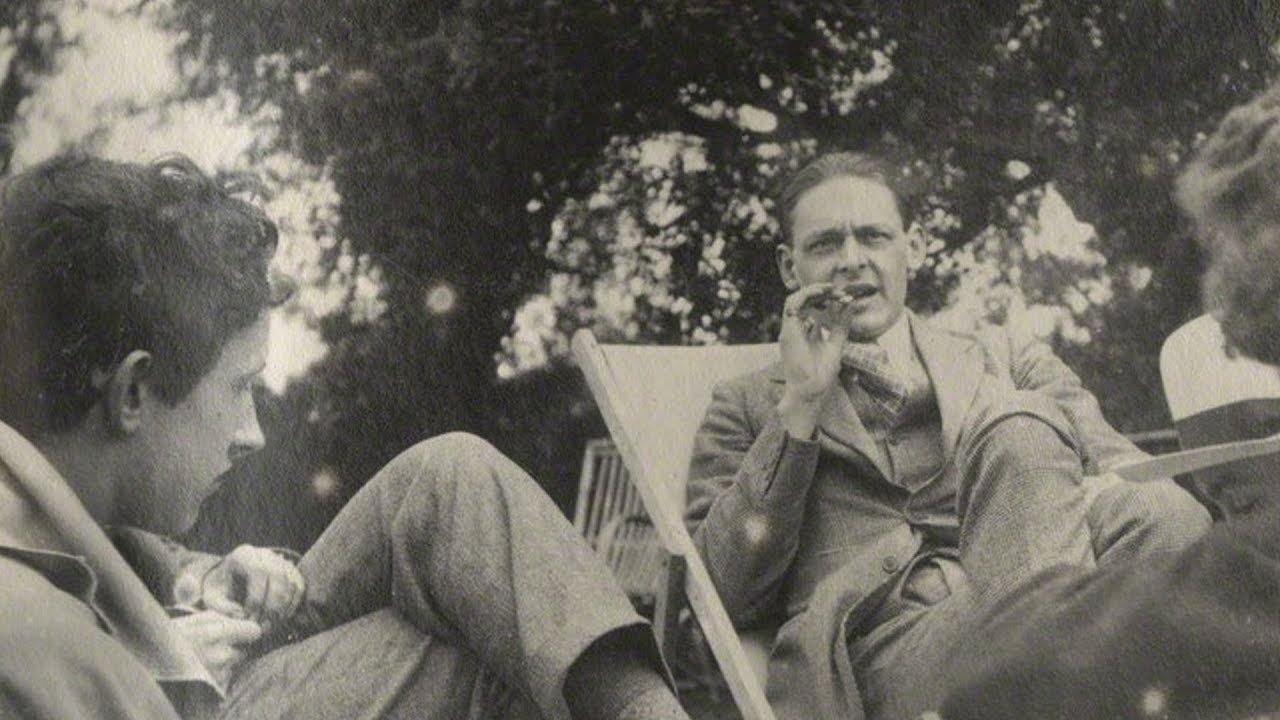

T.S. Eliot in 1923. (Photograph by Lady Ottoline Morrell)

The Dry Salvages is a group of three rocks off the coast of Rockport, near Straitsmouth Island. In a very rocky landscape, they may not be particularly remarkable if not for the fact that T.S. Eliot titled a poem after them and used them as one of its central images, fascinated by their ability to be both a helpful landmark and a dangerous, lurking obstacle to those sailing by.

“And the ragged rock in the restless waters,

waves wash over it, fogs conceal it;

On a halcyon day it is merely a monument, in navigable weather it is always a seamark

To lay a course by: but in the sombre season

Or the sudden fury, is what it always was.”

When he composed “The Dry Salvages,” the third of his Four Quartets, about that trio of rocks off the coast of Rockport, it was 1940 and Eliot had not lived in the United States for a quarter of a century. He had renounced his American passport and become a British subject in 1927. And yet the imprint of his childhood summers on Eastern Point in Gloucester clearly remained strong, showing up in the title and central image of this great late work.

In his talk “The Influence of Landscape Upon the Poet” Eliot spoke about “The Dry Salvages” and staked his claim to being a New England poet, based on what he described as the significant influence of his time on Cape Ann. Now the house where he spent those summers is once again nurturing and inspiring literary talent, as a writer’s retreat run by the T.S. Eliot Foundation.

Despite the fact that Eliot self-identified as a New England poet, won the Nobel prize, and is the author of what is arguably modernism’s most famous poem, his reputation in the country of his birth has fallen in recent years.

Cats is the fourth longest-running musical in Broadway history. But who remembers that the musical is based on a book by T.S. Eliot? The familiar strains of “Memory” and “Magical Mr. Misstoffelees” mean that more people know some lines of Eliot than are aware of it. That is one of the reasons that Clare Reihill, director of the Eliot Foundation, was interested in purchasing the house when it came on the market in 2015.

She explained to me that recognition and respect of Eliot is very high in England, where he placed first in a 2009 BBC poll of the country’s favorite poet.

“If a similar poll were run in America would he even be placed?” she mused. “I doubt it.”

Wanting to “re-ignite interest” in Eliot in America, Reihill purchased the estate and transformed it into a writer’s retreat which hosts up to six poets, playwrights, and essayists at a time. Fellowships are awarded by invitation only, based on recommendations from contacts in the publishing world.

The retreat runs from April through the end of October and the each season is opened with a reading and reception at the house. This year’s reception took place on a moody, rainy night in April which did put one in mind of those famous opening lines of “The Waste Land”, and featured a reading by Ocean Vuong, the winner of the 2018 TS Eliot prize, which is also a project of the foundation.

Members of the community were invited to the reading and a reception, and allowed to explore the house, including the upstairs bedrooms where the writers stay. There are six bedrooms on the second floor, and another little room, too small to comfortably hold a double bed that is set up as an office: as he was the youngest child, this was Eliot’s room.

• • •

Eliot’s father had the large, shingled house built to accommodate his large family (Eliot was the youngest of seven children) and it was completed in 1896. He was a successful brick manufacturer in Saint Louis, but his father, a Unitarian minister, was from Massachusetts and the family liked to spend their summers back East.

Prior to owning their own summer house, the family had stayed at the Hawthorne Inn and cottages in East Gloucester for their sojourns east. At the time, the Eastern Point Associates, which had purchased the former farmland and divided into plots for houses, had only recently been formed. The Eliot house was built a decade before Henry Sleeper bought his plot and began building the house that would become Beauport. When Eliot Sr. built it, the property ran all the way down to the water and had an unobstructed view of all of Eastern Point.

Now, there is another property across the street, on the water side, but the house is very private, sitting well back from the road, surrounded by large granite boulders. After purchasing the home from its longtime owner, Dana Hawkes, and engaging her as director of the retreat, the foundation renovated the home for its new purpose. Their careful restoration was awarded a 2018 Preservation award by the Gloucester Historical Commission, which lauded “the Estate’s distinguished restoration of the Eastern Point house and its literary mission for the property,” and noted that “The Eliot Estate’s plan to provide residence to aspiring writers will encourage continued growth in the field of literature and contribute to the city as a whole.”

• • •

Last summer was only the retreat’s second season, but already its scope is expanding: in addition to the opening reception and the writers-in-residence, this spring the house hosted a group of MFA students from UMass Boston for a day, a sort of mini-retreat.

Dr. Lillian-Yvonne Bertram, the Professor of Creative Writing at UMass Boston who organized the outing, felt that Eliot house was the perfect place for the program’s annual retreat. Explaining both the importance of a retreat and the significance of Eliot house itself, she wrote: “What I aim to provide to our students (who hold down numerous jobs and are so tender and kind) is a day away from the rush and crush, to spend time in quiet reflection and inspiration, to look out on the same scenes that inspired such a literary giant as Eliot. They are in a graduate writing program, but they don't always find time to write among the demands of life and this was a great opportunity to have them do just that and in an incredible house and landscapes.”

Reihill was very happy to be approached by Bertram and hopes that more colleagues in academia will propose similar collaborations to use the property. She wants the retreat to be involved in the community and to be useful and inspiring not just to professional writers, but to MFA students, college students, and schoolchildren.

Just as Eliot was fascinated by the duality of the Dry Salvages, their ability to be both helpful and dangerous, there is an interesting duality in the idea of a writer’s retreat as a place that enriches its community. The point of it is to get away, to retreat is to withdraw, and that very sense of isolation and peace is what writer’s retreats offer: the ability to focus exclusively on the work at hand instead of on the other demands of life.

Before building the house on Eastern Point, the Eliot family summered at Rocky Neck’s Hawthorne Inn & Cottages, above.

Eliot House does host its annual season-opening reading, an outward facing event, and it plans to continue to invite local groups in to work in the space, as it did with the UMass Boston students. But retreats are also always reaching beyond their particular group and their particular moment: they are about connecting with literary history and connecting with other contemporary writers, as the fellows at Eliot house do with each other over dinner.

As the retreat continues, its past and current fellows will be part of a sort of literary club, all contributing to the aura of the house. By adding their own legacy to Eliot’s, they will help to keep his alive. And even if in retreat, their presence on Eastern Point will help continue its history as a place for artists and writers, its reputation as a place whose landscape and culture are conducive to creative endeavors.

And perhaps, just like the ur-fellow himself, Thomas Stearns, one of or two of them may even be inspired by things like “the more delicate algae and the sea anemone” to include some glints and glimpses of Cape Ann in their work.

Paul Cary Goldberg is a Gloucester-based photographer whose work is in the collections of the DeCordova Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and many others.

▶︎ For more information on the T.S. Eliot House and Foundation, visit their website.